- In the painting, Christina Olson has her head turned so we can’t see her face. Did that give you freedom to write about her in a way that you wouldn’t have had if her face was visible?

- Before doing your research for this novel were you already interested in Andrew Wyeth’s artwork? Or did you pick the story and then start looking into his work?

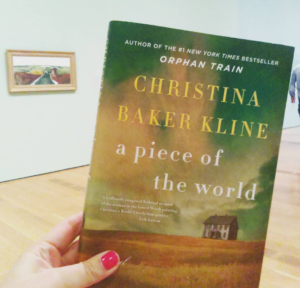

- You write that you became aware of Andrew Wyeth’s painting Christina’s World in your childhood. What does it mean to you, and what do you see as its place in American art history?

- Wyeth isn’t a painter universally liked by critics but he’s very popular among the general public. Robert Hughes calls him “America’s uncontested champion pictorial puritan.” What do you see as the painting’s place in American art history?

- Do you have any favorite explorations of artist-muse relationship — in literature or any other medium?

- What is most compelling about Wyeth’s works? What is the process for developing this inspiration into a novel?

- Other than the central character in your first novel, Sweet Water, who is a sculptor, you haven’t written about the act of artistic creation – or about being an artist’s muse. Was this difficult to do in A Piece of the World? Were you able to tap into anything from your own experience?

- In the painting, Christina Olson has her head turned so we can’t see her face. Did that give you freedom to write about her in a way that you wouldn’t have had if her face was visible.

Absolutely. She’s enigmatic because we don’t know who she is or what she’s thinking. I think you could say that’s what my book is about. What would it look like if the woman in the field turned her head?

- Before doing your research for this novel were you already interested in Andrew Wyeth’s artwork? Or did you pick the story and then start looking into his work?

I had grown up seeing that painting when I was young. It was also sort of widely popular when I was growing up. You know a lot of girls had it on their walls, it was a poster people had. It was just a well known image and I didn’t know much about Andrew Wyeth beyond that until I started going to museums and learning about him, about who he was and what the whole story was. So, I guess I would say I learned about the painting first.

- You write that you became aware of Andrew Wyeth’s painting Christina’s World in your childhood.

It’s come to mean more to me. It did have a meaningful place in my childhood. As I began researching the painting, I was afraid I would get tired of it, but I didn’t. It became deeper and deeper with each viewing…

- Wyeth isn’t a painter universally liked by critics but he’s very popular among the general public. Robert Hughes calls him “America’s uncontested champion pictorial puritan.” What do you see as the painting’s place in American art history?

Well, I know that his reputation is changing. Wyeth was famous in his lifetime, decorated with awards. In the ‘60s his reputation took a hit with the rise of Pop Art and abstract art, movements away from figurative painting. He was derided as conservative and even reactionary. Art historians began dismissing him.

There’s a new book called Rethinking Andrew Wyeth. It’s a collection of essays by curators and historians about Wyeth’s place in 20th century art in America and he’s not exactly like Norman Rockwell but like Rockwell his work is being reevaluated. It’s also being re-contextualized and I would say furthermore that what he was trying to do is now called metaphoric realism, forged in the ‘30s and ‘40s when there were influences of American realism and figurative surrealism.

Like John Currin today, Wyeth plays with a pointillist approach but his work is almost more sinister. He was fascinated with ghosts, goblins, witches.

- Do you have any favorite explorations of artist-muse relationship — in literature or any other medium?

In the beautifully observed novel “Girl with a Pearl Earring,” Tracy Chevalier imagines the life of the anonymous girl who posed for one of Vermeer’s best-known works. Griet — who has been farmed out as a maid to help support her family — is quiet and hardworking but also bright and inquisitive. Her interest in art catches the painter’s attention, and when he asks her to mix his paint and model for him, it alarms not only her pious family but his jealous wife. I appreciate that Chevalier clearly did her research, but it never threatened to overwhelm the story.

- What is most compelling about Wyeth’s works? What is the process for developing this inspiration into a novel?

As a fairly new book called “Rethinking Andrew Wyeth” (ed. David Cateforis) points out, Andrew Wyeth heightened the ordinary to reveal fundamental qualities of human existence. He cared deeply about his subjects, which I think comes through in his work. I studied and read about his work, as well as interviewed museum curators, Olson house tour guides and relatives as preparation for writing this novel.

- Other than the central character in your first novel, Sweet Water, who is a sculptor, you haven’t written about the act of artistic creation – or about being an artist’s muse. Was this difficult to do in A Piece of the World? Were you able to tap into anything from your own experience?

One of the wonderful things about being a writer is that you’re constantly dredging up some arcane knowledge or long-forgotten experience, rediscovering old passions and interests. In my teens I fancied myself an artist; I hung out with the eccentric art teacher at my high school, painted still lifes and portraits and landscapes in watercolor and acrylics, took private lessons, won some blue ribbons for my earnest renderings. My lack of talent did little to dampen my enthusiasm. In college I thought I’d continue, but, like Salieri, I quickly realized that while I had the ability to appreciate art, I wasn’t actually very good. Instead of painting, I studied art history. As I wrote A Piece of the World I drew on my love of painting and my understanding of 20th-century American art to create Wyeth’s character.