If you’d like to learn more about the inspiration and research for The Exiles, consider attending an event during Christina’s virtual book tour. Click here for more information.

I didn’t realize until I’d finished writing The Exiles that I’d twined together three disparate strands of my own life history to tell the story: a transformative six weeks in Australia in my mid-twenties; the months I spent interviewing mothers and daughters for a book about feminism; and my experience teaching women in prison.

As a grad student living in Virginia many years ago, I learned that the local Rotary Club was sponsoring fellowships to Australia. I’d been obsessed with the place since my father, a historian, gave me his marked-up copy of Robert Hughes’ 1986 book The Fatal Shore: The Epic of Australia’s Founding. As one of four Rotary “ambassadors,” I fell in love with the wide-open vistas, the vividly colored birds and flowers, and the offhanded friendliness that seemed to be a hallmark of the culture. Several years later, in the mid-1990s, I wrote a book with my mother, a women’s studies professor, called The Conversation Begins: Mothers and Daughters Talk About Living Feminism. The interviews we did taught me a powerful lesson about the value of women telling the truth about their lives. Building on that experience, I later created a proposal to teach memoir writing at a women’s prison in New Jersey. My class of 12 maximum-security inmates wrote poems, essays, songs, and stories; it was the first time many of them had shared the most painful and intimate aspects of their experience.

When I began to research the experience of convict women in nineteenth-century Australia for The Exiles, I recalled how, on my long-ago visit, the Aussies I met had been happy to talk about their national parks, their pioneering spirit, and their barbecued shrimp, but seemed reluctant to discuss some of the more complicated aspects of their history. When I did press them to talk about race and class, I was gently, subtly, rebuked. Returning to Hughes’ 600-page book, I discovered that only one chapter, “Bunters, Mollies and Sable Brethren,” specifically addressed the experiences of convict women and Aboriginal people. I thought of the prisoners I’d taught in New Jersey who’d been both terrified and relieved to tell their stories – and how searingly honest they’d been.

All of this led me to write a novel that showcased a variety of perspectives, from a naïve London governess, to a streetwise hustler, to a young Scottish midwife, to an Aboriginal girl caught between cultures. My characters face hardship and repression; as in the real-life accounts I studied, some stories end tragically. But for many convict women from socially stratified Britain and Ireland, Australia eventually became a place of reinvention. Survival and perseverance are an important part of my story.

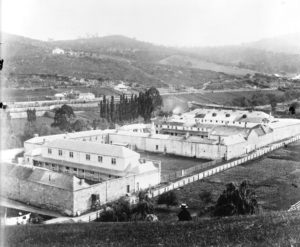

Today, about 20% of Australians – a total of nearly five million people – are descended from transported British convicts. But only recently have many Australians begun embracing their convict heritage and coming to terms with the legacy of colonization. I was lucky to research this book when I did; a number of historic sites and museum exhibits are new. Though descendants of convicts now make up three quarters of Tasmania’s white population, when I first visited the island several years ago the convict museum at The Cascades Female Factory was only three years old. The permanent exhibitions showcasing Aboriginal history, art, and culture at the Tasmanian Museum & Art Gallery had opened two weeks earlier. In addition to these places, I visited Runnymede, a National Trust site preserved as an 1840s whaling captain’s house, in New Town, Tasmania, the Hobart Convict Penitentiary, the Richmond Gaol Historic Site, the Maritime Museum of Tasmania, and convict sites and museums in Sydney and Melbourne.

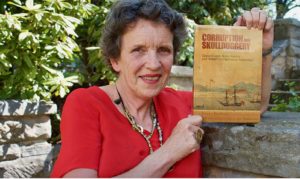

As I began to delve into the topic, I found the website of Dr. Alison Alexander, a retired professor at the University of Tasmania who has written or edited 33 books, including The Companion to Tasmanian History; Tasmania’s Convicts: How Felons Built a Free Society; Repression, Reform & Resilience: A History of the Cascades Female Factory; Convict Lives at the Cascades Female Factory; and The Ambitions of Jane Franklin (for which she won the Australian National Biography Award). These books became primary sources for this novel. Dr. Alexander, who is herself descended from convicts, became an invaluable resource and a dear friend. She gave me a massive reading list and I devoured it all, from information about the prison system in England in the 1800s to essays about the daily tasks of convict maids to contemporaneous novels and nonfiction accounts. On my research trips to Tasmania, she introduced me to experts, took me to historic sites, and even fed me in her home. Most of all, she read my manuscript with a keen and expert eye. I am grateful for her rigor, her encyclopedic knowledge, and her kindness.

Notable among the contemporary books I read on the subject of convict women are Abandoned Women: Scottish Convicts Exiled Beyond the Seas, by Lucy Frost; Depraved and Disorderly: Female Convicts, Sexuality and Gender in Colonial Australia, by Joy Damousi; A Cargo of Women: Susannah Watson and the Convicts of the Princess Royal, by Babette Smith; Footsteps and Voices: A historical look into the Cascades Female Factory, by Lucy Frost and Christopher Downes; Notorious Strumpets and Dangerous Girls, by Philip Tardif; The Floating Brothel: The Extraordinary True  Story of Female Convicts Bound for Botany Bay, by Sian Rees; The Tin Ticket: The Heroic Journey of Australia’s Convict Women, by Deborah Swiss; Convict Places: A Guide to Tasmanian Sites, by Michael Nash; To Hell or to Hobart: The Story of an Irish Convict Couple Transported to Tasmania in the 1840s, by Patrick Howard; and Bridget Crack, by Rachel Leary. Books I read about Australian history and culture include, among others, In Tasmania: Adventures at the End of the World, by Nicholas Shakespeare; Thirty Days in Sydney: A Wildly Distorted Account and True History of the Kelly Gang, by Peter Carey; The Songlines, by Bruce Chatwin; and The Men that God Forgot, by Richard Butler.

Story of Female Convicts Bound for Botany Bay, by Sian Rees; The Tin Ticket: The Heroic Journey of Australia’s Convict Women, by Deborah Swiss; Convict Places: A Guide to Tasmanian Sites, by Michael Nash; To Hell or to Hobart: The Story of an Irish Convict Couple Transported to Tasmania in the 1840s, by Patrick Howard; and Bridget Crack, by Rachel Leary. Books I read about Australian history and culture include, among others, In Tasmania: Adventures at the End of the World, by Nicholas Shakespeare; Thirty Days in Sydney: A Wildly Distorted Account and True History of the Kelly Gang, by Peter Carey; The Songlines, by Bruce Chatwin; and The Men that God Forgot, by Richard Butler.

A number of articles and essays were useful, especially “Disrupting the Boundaries: Resistance and Convict Women,” by Joy Damousi; “Women Transported: Myth and Reality,” by Gay Hendriksen; “Whores, Damned Whores, and Female Convicts: Why Our History Does Early Australian Colonial Women a Grave Injustice,” by Riaz Hassan; “British Humanitarians and Female Convict Transportation: The Voyage Out,” by Lucy Frost; and “Convicts, Thieves, Domestics, and Wives in Colonial Australia: The Rebellious Live of Ellen Murphy and Jane New,” by Caroline Forell. I found a wealth of information online at sites such as Project Gutenberg, Academia.edu, the Female Convicts Research Centre (femaleconvicts.org.au), the Cascades Female Factory (femalefactory.org.au), and the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre (tacinc.com.au).

Nineteenth-century novels and nonfiction accounts I read include The Life of Elizabeth Fry: Compiled from Her Journal (1855), by Susanna Corder; Elizabeth Fry (1884), by Mrs. E.R. Pitman; The Broad Arrow: Being Passages from the History of Maida Gwynnham, a Lifer (1859), by Oline Keese (a pseudonym for Caroline Leakey); For the Term of his Natural Life (1874), by Marcus Andrew and Hislop Clarke; Christine: Or, Woman’s Trials and Triumphs (1856), by Laura Curtis Bullard; and The Journals of George Augustus Robinson, Chief Protector, Port Phillip Aboriginal Protectorate, Volume 2 (1840-1841).