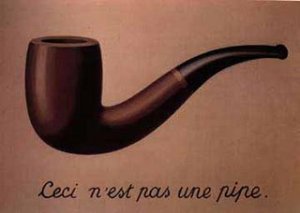

Semiotics is the study of signs, and a sign is anything that stands for something else. It took me a long time to understand this seemingly simple idea.

Semiotics is the study of signs, and a sign is anything that stands for something else. It took me a long time to understand this seemingly simple idea.

The argument goes like this: it is a myth to believe there is any such thing as an objective reality; ‘reality,’ in fact, is a system of signs. As Proust has said, “Everything can be several things at the same time.” Or, to put a finer point on it: the art historian Ernst Gombrich says, “There is no reality without interpretation.”

The British semiotician Daniel Chandler suggests that studying semiotics can make us “more aware of reality as a construction and of the roles played by ourselves and others in constructing it. Meaning is not ‘transmitted’ to us – we actively create it according to a complex interplay of codes or conventions of which we are normally unaware. Becoming aware of such codes is both inherently fascinating and intellectually empowering.”

The process of creating literary fiction, I would argue, is the practice of semiotics. It’s all about signs. Our characters’ reality – an artificial construct to begin with – is freighted with meaning, conscious and unconscious, for the writer, the characters themselves, and ultimately for the reader.

In his preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray, Oscar Wilde wrote, “All art is at once surface and symbol. Those who go beneath the surface do so at their peril.” But these signs and symbols, the dual or multiple meanings, must be subservient to the story, and not the other way around. Otherwise the fictional trance will be broken; the characters will be types and not individuals. The novel will become a treatise.